Tech Deep Dive: Hydrometallurgy vs Pyrometallurgy vs Emerging Recycling Methods — What’s Best for India’s LIB Waste?

>

>

Tech Deep Dive: Hydrometallurgy vs Pyrometallurgy vs Emerging Recycling Methods — What’s Best for India’s LIB Waste?

As India’s electric vehicle fleet expands, a parallel question grows more urgent: how do we extract maximum value from spent lithium-ion batteries while minimizing environmental impact? The answer isn’t just about whether to recycle—it’s about how. The recycling process we choose determines recovery efficiency, environmental footprint, operational costs, and ultimately, whether India can build a truly circular battery economy.

At Nav Prakriti, we’ve studied and implemented various recycling technologies. We’ve witnessed firsthand how process selection shapes outcomes—from the purity of recovered materials to the carbon intensity of operations. As India scales its battery recycling infrastructure, understanding these technological pathways becomes critical for policymakers, investors, and industry players alike.

The Three Pillars: Understanding Core Recycling Approaches

Lithium-ion battery recycling isn’t monolithic. Three primary methodologies have emerged globally, each with distinct advantages and limitations.

✅ Pyrometallurgy represents the oldest industrial approach. This high-temperature process involves smelting batteries at temperatures exceeding 1000°C, melting down components to recover metals like cobalt, nickel, and copper. The extreme heat simplifies processing—no need for extensive disassembly or pretreatment. The entire battery pack can essentially be thrown into a furnace.

But this brute-force simplicity comes at steep costs. Energy consumption is enormous. Valuable materials like lithium and aluminum often end up in slag rather than being recovered. Graphite, which comprises significant battery mass, typically burns off completely. Emissions require sophisticated control systems. And perhaps most importantly, recovery rates for critical materials rarely exceed 60-70%.

✅ Mechanical processing takes the opposite approach—physical separation without chemical transformation. Batteries are shredded, and various mechanical techniques (screening, magnetic separation, density separation) sort components into different material streams. It’s relatively low-energy and straightforward to implement.

The challenge is incomplete separation. You end up with mixed material streams—a “black mass” containing cathode and anode materials jumbled together. Without subsequent chemical processing, recovery of high-purity metals remains limited. Mechanical-only approaches typically achieve 40-50% effective recovery of critical materials, leaving substantial value in residual waste.

✅ Hydrometallurgy represents the middle path—and increasingly, the preferred one. This chemical processing route uses aqueous solutions to selectively dissolve and separate metals. After mechanical pretreatment and thermal deactivation, crushed battery materials undergo chemical leaching. Subsequent purification steps isolate individual metals: lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, and others.

The advantages are compelling. Hydrometallurgical processes can recover over 95% of valuable materials, including lithium—something pyrometallurgy struggles with. Energy consumption is substantially lower than high-temperature smelting. Emissions are more easily controlled. The process yields battery-grade materials suitable for direct reintegration into new cell production.

These strengths explain why hydrometallurgy is forecast to dominate India’s battery recycling landscape. As volumes scale and material recovery economics become central to business viability, the superior extraction efficiency of hydrometallurgical routes becomes decisive.

The Limitations We Must Acknowledge

Yet no current technology is perfect. Even advanced hydrometallurgical processes face challenges that India must address.

✅ Energy intensity remains significant, even if lower than pyrometallurgy. Chemical processing requires heating, mixing, and multiple purification stages. In a country still heavily reliant on coal power, the carbon footprint of hydrometallurgical recycling deserves scrutiny and continuous optimization.

✅ Chemical consumption is substantial. Acids, bases, solvents, and precipitating agents are consumed in large quantities. While many can be recovered and reused, there’s inevitable loss. Managing chemical inputs sustainably—including their own production footprint—is an ongoing imperative.

✅ Wastewater management presents operational complexity. Aqueous processing generates liquid waste streams requiring treatment before disposal. While modern facilities achieve high water recycling rates, ensuring zero environmental discharge demands constant vigilance and investment.

✅ Cost competitiveness remains challenging when virgin material prices fluctuate. When lithium or cobalt prices crash, recycled materials must compete with cheap mining output. Only process efficiency, scale economies, and supportive policy can ensure recycled material markets remain viable through commodity price cycles.

Perhaps most critically, current commercial processes—whether hydro or pyrometallurgical—often focus primarily on cathode metals (lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese) while giving less attention to other valuable components. This is where emerging methods offer intriguing possibilities.

Beyond Convention: Emerging Technologies Reshaping the Field

The next generation of battery recycling is moving beyond simple metal recovery toward comprehensive material reuse and efficiency gains that reshape the economics.

✅ Direct component reuse represents one of the most promising frontiers. Current collectors—the aluminum and copper foils that conduct electricity within cells—are typically recycled as scrap metal, losing their engineered properties. Research now demonstrates these foils can be recovered intact, cleaned, and directly reused in new battery production. The energy and material savings are substantial: producing new aluminum and copper foils is energy-intensive; reusing existing ones cuts both costs and carbon footprint.

Similar principles apply to other components. Separators, if undamaged, could potentially be cleaned and reused. Even certain electrode materials might be directly regenerated rather than fully broken down and reconstituted. This “direct recycling” or “direct cathode recycling” approach aims to preserve the value added during manufacturing rather than returning everything to commodity metals.

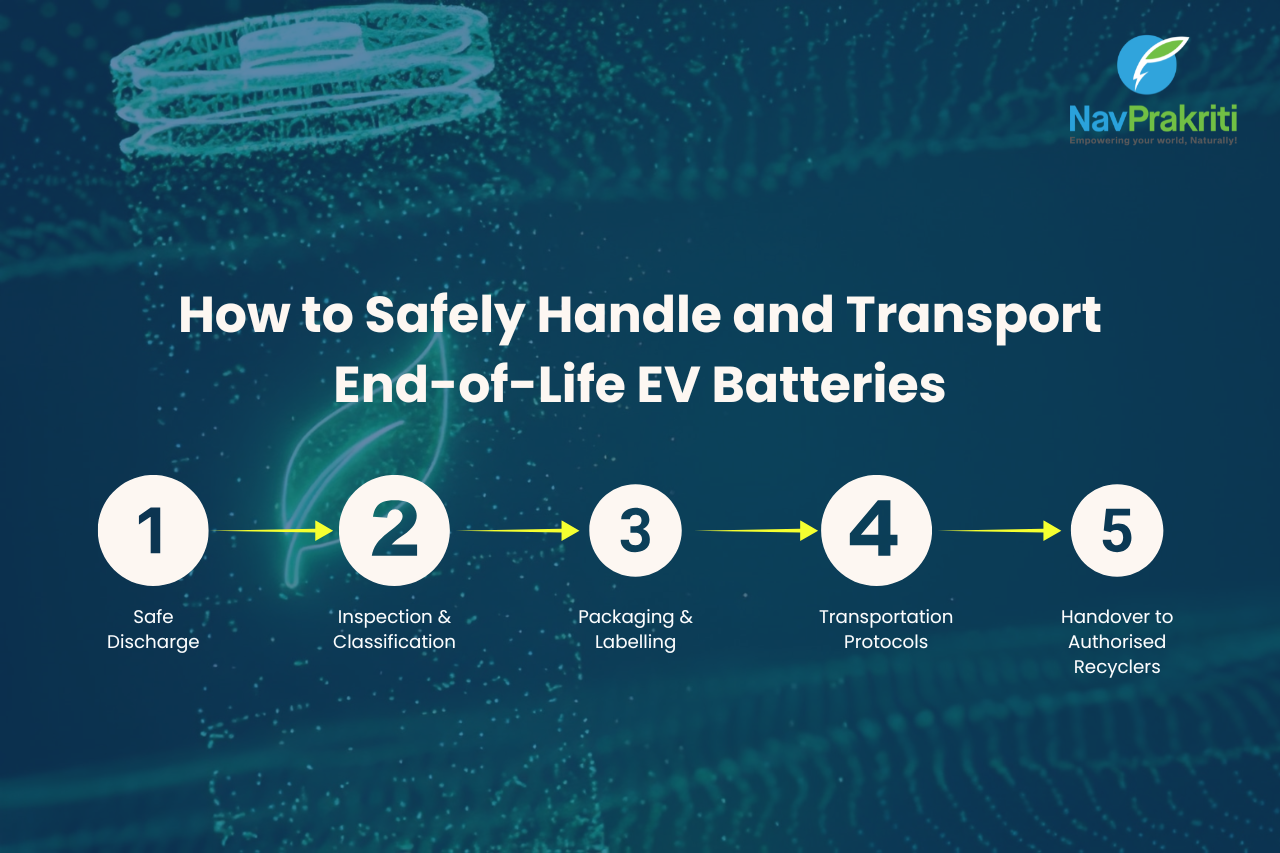

✅ Automated disassembly systems address one of recycling’s most dangerous bottlenecks. EV battery packs are complex assemblies—hundreds of individual cells, cooling systems, wiring harnesses, and battery management electronics, all designed for durability, not easy disassembly. Manual dismantling risks electric shock, chemical exposure, and fire.

Robotics and automation offer solutions. Advanced systems use computer vision to identify battery pack configurations, robotic arms to systematically disassemble modules, and automated testing to assess cell condition. Some cells may still have substantial capacity—suitable for second-life applications rather than immediate recycling. Automation enables this differentiation at scale while protecting workers.

In India’s context, where labor costs favor manual processes but safety regulations are tightening, automated disassembly represents a critical investment area. The consistency it provides—every pack disassembled identically, every cell properly categorized—improves downstream processing efficiency dramatically.

✅ Advanced separation techniques are emerging beyond conventional mechanical methods. Froth flotation, electrostatic separation, and novel density-based systems achieve cleaner separation of graphite from cathode materials in black mass. This improves the purity of inputs to hydrometallurgical processing, reducing chemical consumption and increasing recovery rates.

✅ Solvent-based selective extraction offers alternatives to traditional acid leaching. Certain organic solvents can selectively dissolve specific metals, potentially reducing energy and chemical inputs. While still largely at research scale, these approaches may offer advantages for particular battery chemistries.

India’s Optimal Path: A Hybrid Strategy

Given India’s specific context—rapidly growing EV adoption, limited domestic mineral resources, need for employment generation, tightening environmental standards, and cost sensitivity—what’s the right technological approach?

The answer isn’t choosing a single method but architecting a hybrid system that captures the strengths of multiple approaches while mitigating individual weaknesses.

✅ Foundation: Hydrometallurgical Processing for Metal Recovery

Hydrometallurgy should remain the core process for extracting battery-grade lithium, cobalt, nickel, and manganese. The superior recovery rates—critical when 80% of India’s lithium and cobalt is imported—justify the process complexity. As India builds domestic battery manufacturing capacity, supplying these facilities with high-purity recycled materials reduces import dependence and improves supply chain resilience.

Investment in process optimization should focus on reducing chemical and energy inputs. Closed-loop water systems, solvent recovery, and integration with renewable energy can significantly improve the environmental profile of hydrometallurgical operations.

✅ Strategic Addition: Direct Reuse of Current Collectors and Components

Rather than melting down aluminum and copper foils as scrap, Indian recyclers should invest in technologies to recover these components intact. The energy savings alone—avoiding the production of new foils—improve process economics and reduce carbon intensity. As volumes scale, the cost differential between recovered-and-reused foils versus new production will become a competitive advantage.

This requires additional process steps—careful mechanical separation, cleaning protocols, quality testing—but the value proposition is compelling. Nav Prakriti and other forward-looking recyclers should pioneer these techniques in India, establishing processes and quality standards that make direct reuse commercially viable.

✅ Critical Investment: Robotic Disassembly Systems

India cannot afford to scale battery recycling on manual disassembly of high-voltage battery packs. The safety risks are unacceptable, and the process inconsistency undermines downstream efficiency. Automated disassembly should be a mandatory component of any large-scale recycling facility.

This technology also enables sophisticated triage: identifying cells suitable for second-life applications, separating different battery chemistries for optimized processing, and safely handling damaged or swollen cells that pose fire risks. The data generated during automated disassembly—cell condition, degradation patterns, failure modes—provides valuable feedback to battery manufacturers for design improvement.

✅ Enabling Layer: Digital Integration and Material Tracking

Technology choices must be supported by information systems that track materials through the recycling process. Digital battery passports should interface with recycling facility systems, providing incoming material specifications. Process control systems should monitor recovery rates in real-time, enabling rapid optimization. Output material tracking should create verifiable chain-of-custody, supporting premium pricing for certified recycled content.

Metrics That Matter: Measuring Success

How do we evaluate whether India’s technology choices are working? Several metrics deserve continuous monitoring:

✅ Overall material recovery rate: The percentage of valuable materials successfully extracted and returned to productive use. India should target 90%+ recovery of lithium, cobalt, nickel, manganese, copper, and aluminum.

✅ Energy intensity: kWh consumed per kilogram of battery processed. This directly impacts both operating costs and carbon footprint.

✅ Water consumption and recycling rate: Particularly critical in water-stressed regions where facilities may be located.

✅ Worker safety incidents: Automation and proper processes should drive this toward zero.

✅ Economic competitiveness: Cost per kilogram of recovered material versus virgin material cost. The gap determines whether recycled content is economically attractive without subsidy.

✅ Environmental compliance: Zero discharge of hazardous materials, minimized solid waste, controlled emissions.

The Road Ahead

India stands at a pivotal moment. The decisions we make now about recycling technology will shape our battery economy for decades. Choose poorly—prioritizing cheap, low-recovery processes—and we’ll perpetually depend on imports while leaving value in waste. Choose wisely—investing in high-recovery, increasingly automated systems—and we build genuine circularity.

At Nav Prakriti, we’re committed to the latter path. Our facilities combine advanced hydrometallurgical processing with increasing automation and continuous process improvement. We’re exploring direct component reuse and working with research institutions to bring emerging technologies to commercial scale in India.

But technology alone won’t suffice. Success requires supportive policy—EPR regulations that incentivize high recovery rates, standards that ensure environmental compliance, and procurement preferences for recycled materials. It requires collaboration between recyclers, battery manufacturers, and vehicle OEMs to optimize design-for-recycling. And it requires patience—building world-class recycling infrastructure takes time and sustained investment.

The goal is clear: an India where every battery entering the waste stream is processed through formal, high-efficiency recycling systems. Where recovered materials supply a substantial share of new battery production. Where recycling is seen not as waste management but as advanced manufacturing—producing the raw materials for our electric future.

The technology to achieve this exists. The question is whether India will deploy it fast enough and at sufficient scale to match our EV ambitions. The answer depends on choices being made right now—by companies like ours, by policymakers, and by every stakeholder in India’s electric mobility revolution.

.png)

Leave a Reply